Stress is a leading factor in poor sleep, according to new research from Oklahoma State University. Their study, “Back Pain, Sleep Quality and Perceived Stress Following Introduction of New Bedding Systems,” published in the March 2009 Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, suggests that improved sleep quality not only reduces stress, but also helps us manage everyday stress. “When you’re stressed, and similarly when you are tired, every aspect of your waking life is affected, from work to personal relationships and even concentration,” says Better Sleep Council spokesperson Lissa Coffey. “Controlling stress and getting a good night’s rest start by evaluating your lifestyle and creating a healthy daily regimen that you can stick to”.

Category: How Stress affects us

Noise and silence

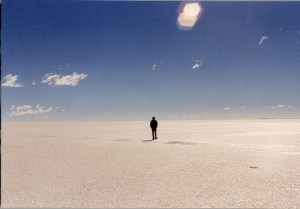

For some people today is the last day of the holidays before the return to work tomorrow. After a period of rest it will be back to the stress and rush of deadlines and meetings, or commuting, and noise. Often the background noise of the city is so pervasive that we can get to a stage that we do not even notice it. As the continual playing of Christmas music in shops over the past few weeks demonstrates, we can’t seem to live without some background sound. We have created an acceptance of our noisy world in spite of some evidence that it is making us ill physically and psychologically.

For some people today is the last day of the holidays before the return to work tomorrow. After a period of rest it will be back to the stress and rush of deadlines and meetings, or commuting, and noise. Often the background noise of the city is so pervasive that we can get to a stage that we do not even notice it. As the continual playing of Christmas music in shops over the past few weeks demonstrates, we can’t seem to live without some background sound. We have created an acceptance of our noisy world in spite of some evidence that it is making us ill physically and psychologically.

For example, a study by Cornell University published in the Journal of Applied Psychology in 2001 found that low-level office noise increases health risks and lowers task motivation for people who work there. The study found that workers in a noisy office experienced significantly higher levels of stress and made 40 percent fewer attempts to solve an unsolvable puzzle than a similar group in quiet working conditions. The effect of this stress meant that the same workers were less likely to take breaks or make healthy adjustments which would help them in the long term.

As one of the researchers, Gary Evans, an expert on environmental stress, stated: “One possible reason is that under stress, people focus in on their main task or activity. This focusing leads to less flexibility in considering alternatives during decision making, for example. Perhaps if people are working at a task and are under more stress, they become more focused on the task itself, not being as cognizant as they should be to change their posture or take a break.”

In many cases we have no control over our external environment of the noise of a city. However we do have choices in our internal environment and in our own homes. Setting aside time for meditation creates an interior silence. However we can support this by reducing some of the noise that surrounds us, turning off the radio in the car or the TV in the house. We can start this slowly, for short periods, gradually increasing the length of time. It may be that soon we will begin to look forward the periods of silence we have built into our day and even want more. Research supports the fact that this is a step towards becoming more relaxed and less tense even in the midst of our noisy world.

How is it possible to reach inner silence? Sometimes we are apparently silent, and yet we have great discussions within, struggling with imaginary partners or with ourselves. Calming our souls requires a kind of simplicity: “I do not occupy myself with things too great and too marvellous for me.” Silence means recognising that my worries can’t do much. Silence means leaving what is beyond my reach and capacity. A moment of silence, even very short, is like a holy stop, a sabbath rest, a truce from worries.

Taize The Value of Silence

Help for Helpers

Training in mindfulness meditation can alleviate burnout experienced by many in the helping professions and improve their well-being, University of Rochester Medical Center researchers report.

Training in mindfulness meditation can alleviate burnout experienced by many in the helping professions and improve their well-being, University of Rochester Medical Center researchers report.

The training also can expand a physician’s capacity to relate to patients and enhance patient-centered care, according to the researchers, led by Michael S. Krasner, M.D., associate professor of Clinical Medicine.”From the patient’s perspective, we hear all too often of dissatisfaction in the quality of presence from their physician. From the practitioner’s perspective, the opportunity for deeper connection is all too often missed in the stressful, complex, and chaotic reality of medical practice,” Krasner said.

“Enhancing the capacity of the physician to experience fully the clinical encounter—not only its pleasant but also its most unpleasant aspects—without judgment but with a sense of curiosity and adventure seems to have had a profound effect on the experience of stress and burnout. It also seems to enhance the physician’s ability to connect with the patient as a unique human being and to center care around that uniqueness”

Seventy physicians from the Rochester, N.Y., area were involved in the study and training. The training involved eight intensive weekly sessions that were 2 ½ hours long, an all-day session and a maintenance phase of 10 monthly 2 ½-hour sessions.

Edward A. Stehlik, M.D., of the New York branch of the American College of Physicians and an internist who practices near Buffalo, said the training was “the most useful thing I’ve done since my medical training to help me in my practice of medicine.”

“If you asked my patients, I think they would say I listen more carefully since the training and that they feel they can explain things to me more forthrightly and more easily,” Stehlik said. “Even the brief moments with patients are more productive. Are there doctors who desperately need this training? Yes, absolutely.”

ScienceDaily (Sep. 23, 2009)

Stress

The pace of life today can cause people to push their minds and bodies to the limit, often at the expense of physical and mental well-being. According to the Mind/Body Medical Institute at Harvard University, 60 – 90% of all medical visits in the US are for stress-related disorders.